NEH grant largest federal grant in Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research’s history

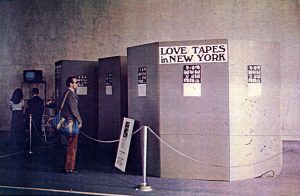

Decades before YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and the selfie sensation, independent video artist Wendy Clarke invited hundreds of people into a video booth inside the World Trade Center and—one by one, for exactly three minutes each, and in their own voices—to describe what love meant to them.

“Participants in the 1980 World Trade Center Love Tapes were allowed to choose the music they wanted for the background and then, in front of a camera and largely unrehearsed, they shared their stories and raw emotions—joy, loss, belonging, loneliness, and sadness,” says Eric Hoyt, Kahl Family Professor of Media Production, Professor of Film, Media, and Cultural Studies, and director of the Media History Digital Library and the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research (WCFTR).

Today, the WCFTR houses Clarke’s collection. A $298,292 Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant awarded this year from the National Endowment for the Humanities will make Clarke’s works more accessible. This is the largest federal grant in the WCFTR’s 63 -year history, according to Hoyt.

The grant will fund digitization of 863 original videotapes recorded in 13 different formats and produced by Clarke for a series of 15 video projects from the 1980s and 1990s— including the Love Tapes—that explored themes of love, community, culture, and self-reflection across multiple underrepresented communities.

Faces and voices on Clarke’s Love Tapes came from a diverse range of ethnic backgrounds and included New York City’s gay, lesbian, and transgender communities. The Love Tapes in turn became the basis for one of Clarke’s many video-based works of art, appearing in museum galleries and on PBS stations.

Hoyt notes the tapes have become even more historically significant, having been recorded in a space that no longer exists because of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

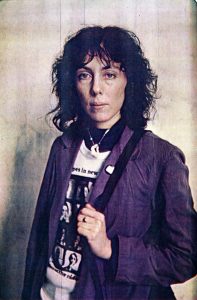

Clarke is the daughter of dancer and  independent filmmaker Shirley Clarke, who was an esteemed women worked in the field. Shirley’s feature debut, “The Connection,” was recently screened during the Wisconsin Film Festival. Based on Jack Gelber’s 1959 play, the film within a film is set in a rundown New York flat where a director and camera operator are documenting a group of heroin addicts, including some jazz musicians who play as they wait for their supplier to arrive.

independent filmmaker Shirley Clarke, who was an esteemed women worked in the field. Shirley’s feature debut, “The Connection,” was recently screened during the Wisconsin Film Festival. Based on Jack Gelber’s 1959 play, the film within a film is set in a rundown New York flat where a director and camera operator are documenting a group of heroin addicts, including some jazz musicians who play as they wait for their supplier to arrive.

“Our long-standing relationship with Shirley, dating back to the 1970s, was one of the big reasons why Wendy chose the WCFTR for her collection,” said Mary Huelsbeck, who helps facilitate acquisitions for the WCFTR in her role as assistant director. In 2017, Wendy d onated her collection of tapes, papers, photographs, and other records to the WCFTR.

onated her collection of tapes, papers, photographs, and other records to the WCFTR.

The WCFTR is one of the world’s major archives of research materials relating to the entertainment industry. It maintains over 300 hundred collections from outstanding playwrights, television and motion picture writers, producers, actors, designers, directors, and production companies.

“We are excited to share the legacy of Wendy’s work – it is unique, vast, and important,” Hoyt says. “In a pre-world wide web era, she was producing participatory media and creating a social and cultural archive.”

Funding from the Friends of the UW-Libraries had previously allowed the WCFTR to digitize and make available 15 hours of Love Tapes on the WCFTR’s Internet Archive page.

“The WCFTR is a real gem on campus and home to one of the largest and most significant collections of media history in the world,” says Florence Hsia, associate vice chancellor for research in the arts and humanities. “This NEH grant will help support the center’s important mission to preserve and deepen our understanding of our history, culture, and society.”

Hoyt credits past WCFTR director, Tino Balio, and other campus visionaries with acquiring, cataloging, and maintaining rich collections of materials relating to modern media industries.

After multiple donations of related papers and memorabilia, the Wisconsin Historical Society formed the Mass Communications History Center in 1955 to develop holdings in this area. In 1960, the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Speech and Theater department formed the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research in order to expand the archives into other areas of media culture with the mission to document twentieth-century performing arts. Today, the WCFTR is part of the university’s Communication Arts department and is operated in partnership with the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Hoyt cites a recent Research Core Revitalization Program grant from the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education as instrumental to its successful NEH grant proposal. The research core grant enabled the AV Data Core to upgrade its digitization capabilities, including purchase of a film evaluator to allow staff to clean films prior to scanning, resulting in much-improved images and preventing dirt and dust from clogging the mechanics of the scanner. The tape evaluator does the same for video materials.

“With proper storage conditions, film can last for over one hundred years,” says Amanda Smith, the WCFTR’s AV archivist and an instructor in UW–Madison’s School of Information. “Video, on the other hand, deteriorates much more quickly and, due to the nature of the medium, we can’t see the image in the same way as a film strip. In light of this, digitization is the only option to avoid losing these unique sounds and images.”

One of the WCFTR’s most important gateways into understanding American culture is the original records of creators such as Clarke, particularly in the field of drama and audiovisual media.

“Wendy Clarke’s archive of the voices of marginalized communities is a model of participatory media culture that preceded the world wide web,” Hoyt says. “The unifying theme of her work was to give ordinary people from diverse backgrounds agency to tell their stories. Our goal now is to take this work that is so fragile, and inspect it, care for it, digitize it in the best quality possible, and make it widely accessible.”

Today, Clarke lives in New Mexico. Hoyt said he contacted her shortly after learning about the NEH award.

“My hope is people watching these videos will realize the connectedness of our humanity regardless of physical and geographical boundaries,” Clarke says. “I’ve been enriched and inspired by all the voices and deep emotions of Love Tape participants—prison inmates who shared their truths, clients in mental hospitals who created wonderful art, and the many others who spoke truthfully about their feelings. I’m so happy their voices will be heard for years and years to come, even long after they have passed from this lifetime.”

Clarke adds that she is grateful to each participant and to Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research for making this possible.

“I can’t think of anything that would make me happier!” she says.

By Natasha Kassulke